Merkle Trees and MAST

Merkelized Abstract Syntax Trees (MAST) is a scheme for pay-to-script-hash outputs which critically improves the privacy and smart contract capabilities of Bitcoin. The locking script of a UTXO can be a complicated contract, with many possible ways of being spent. MAST ensures that the only part of the script that makes it into the blockchain is the part which is actually satisfied by a spender. This is a boon for both privacy and space efficiency, since the unused branches of the script are not stored on-chain. We’ll dive into MAST over the next couple of posts, but in the present one, we’ll start by introducing an important data structure and the one behind MAST: the Merkle tree.

Hashing is a one-way street

For our purposes, a (cryptographic) hash function is a map $H: X \rightarrow M$ from data $x\in X$ to strings $d\in D$ (often known as digests) that has a few important properties:

- $d = H(x)$ is the same length for all $x$,

- Any change in the input, even by one character, will produce a totally different hash output, and

- It is computationally infeasible to find two distinct $x, x'$ such that $H(x) = H(x')$.

Hash functions are a particular class of one-way functions, since it’s easy to compute hash function outputs, but it’s practically impossible to find an input (or preimage) which maps to a particular output. One use for hash functions is validating the integrity of data transmission. If I send you a document $x$, you can confirm that the document was received intact by sending a hash of the document back to me. If the digest you send to me matches my own hash of the document, then I can be certain that you received the document unchanged. The digest will likely be much shorter than the original document (see the first property above), so it will be much more convenient for both of us to check the hash than verify the entire document.

Merkle’s motivation

Often times we want to do more than verify the integrity of some data; we may also want to verify who sent the data. Anyone can compute the SHA-256 hash of a piece of data, e.g. a Bitcoin transaction. But to sign a message is to do so in a way that is unforgeable; the recipient should be able to verify that only a particular sender could have generated the signature.

How might someone sign a message using a hash function? Suppose Alice wants to send one bit of information to Bob. Alice first generates two numbers $x_0, x_1$ randomly, and computes their hashes

$$y_i = H(x_i).$$

Alice can then publish the hashes $y_0, y_1$ for the whole world to see. Then, if Alice’s message is “0”, she will reveal $x_0$ to Bob, and if her message is “1” she’ll send $x_1$ instead. For now, assume Alice sends $x_1$ to Bob. Now Bob can do two things:

- He can verify the integrity of Alice’s message by checking $H(x_1) = y_1$, and

- If Charlie wants to know Alice’s message, Bob can reveal $x_1$ to Charlie. Charlie can then be confident only Alice could have sent the message, because the one-way nature of hash functions ensures that Bob could not have computed $x_1$ on his own.

This is known as a Lamport one-time signature. It’s “one-time” because the random pairs $(x_i, y_i)$ can only be used for one message.

Thus, while we have a scheme for signing messages using only a hash function, it’s pretty expensive. For an $n$ bit message, the sender needs to generate $2n$ random numbers, and a recipient will need to keep track of $2n$ hashes in order to receive the message. If we want to send thousands of kilobyte-size messages, then we need to keep track of millions of hashes.

Merkle’s original tree construction was designed as a clever way to generate digital signatures efficiently. Rather than get into the details of the signature scheme here, we’ll just describe the Merkle tree data structure, and summarize how to can be used to verify the integrity of many data while only storing a single hash. For more information on the signature scheme using Merkle trees, checkout this Wikipedia article.

The Merkle tree from Bitcoin transactions

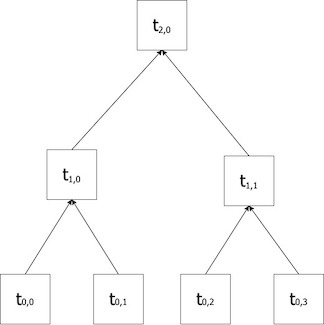

Suppose a Bitcoin block B contains transactions $T_1, T_2, \ldots, T_n$. First, we compute the hashes of the $y_i = H(T_i)$ (any data, like Bitcoin transactions, can be represented as a string of bytes, which can then be fed into a hash function). Next, we construct a binary tree: in our notation, $t_{i,j}$ will be the $j$th node at level $i$ of the binary tree, where nodes at level $0$ are leaves of the tree, and the levels increase as we reach closer to the root of the tree. For example, $t_{0,0}$ is the left-most leaf node of the tree, $t_{1,2}$ is the third node from the left at the first level above the leaves of the tree, etc.

In our tree, the nodes contain hashes; the leaves of the tree are the hashes $y_i$ of the transactions, so that $t_{0,j} = y_j$.

We build up the tree from the bottom level $i = 0$:

-

After we’ve constructed level $i$: $t_{i,0}, \ldots t_{i, k}$, if $k$ is odd, we add a duplicate of $t_{i,k}$ at the end of the level. E.g. if there are only 3 nodes $t_{i,0}, t_{i,1}, t_{i,2}$ at level $i$, we’ll pad it to become $t_{i,0}, t_{i,1}, t_{i,2}, t_{i,2}$.

-

To form the next higher level of the tree, we calculate $t_{i+1, j} = H(t_{i, 2j} || t_{i, 2j+1})$, for $j \leq k/2$ (where $s || t$ is the concatenation of two hashes $s, t$.)

We keep doing this until we reach a level with just a single node; this is the root of the Merkle tree. If this happens at step $i = n$, then we say the tree has height $n$. The hash $r = t_{n,0}$ is the Merkle root.

You can see the implementation of the Merkle tree construction in Bitcoin core here: https://github.com/bitcoin/bitcoin/blob/7fcf53f7b4524572d1d0c9a5fdc388e87eb02416/src/consensus/merkle.cpp

The crucial point is the Merkle root $r$ is a fixed-size string that will serve as a summary of all the transactions in a block.

Merkle proofs

Let’s say I want to confirm that a transaction $T$ is part of the block for which we just constructed the Merkle tree with Merkle root $r$. Without the Merkle tree, maybe I’d download all of the block’s transactions and scan through them until I find $T$ among them or not. This process requires space and time in proportion to the number of transactions in the block.

Given the Merkle root $r$ for the block, all I need instead is a list of hashes $(h_0, h_1, \ldots, h_{n-1})$, one at each level of the tree, such that they “pair” with the hash of $T$ all the way up the tree to the root. More precisely, start with the hash of the transaction $d_0 = H(T)$ and then compute

$$ d_{i+1} = H(d_i || h_i). $$

At the end we’ll have a hash $d_n$. If $d_n = r$, then the transaction $T$ was part of the block. We know this because hash collisions are virtually impossible to produce. Since we demonstrated that there is a sequence with the same height as the tree such that hashes of successive pairs eventually ladder up to the root, we can conclude that this transaction must have been included as one of the leaves of the tree. The sequence of hashes is a path through the tree from the leaves to the root; if there were $N$ transactions in the block, then the height of the Merkle tree and thus the length of this sequence is roughly $log(N)$. Verifying transactions in this way requires far less computation and space than going through the whole transaction list.

Conclusion

The Merkle tree construction allows us to summarize an arbitrary amount of data with a fixed-length hash digest, known as a “Merkle root.” Every Bitcoin block header contains the Merkle root for its transaction data. Checking if a block contains a given transaction becomes possible in logarithmic time instead of linear time in the number of transactions.

In the next post, we’ll explore how Merkle trees can be applied not only to the data of Bitcoin transactions, but also to the code securing the transactions (Bitcoin script), which will allow for more concise blocks and more privacy for users.